Elegance in a Knot – Kaga Mizuhiki

Mizuhiki-orikata is the Japanese art of tying knots decoratively in long twisted strips of Japanese washi paper. An art with roots in ancient China, mizuhiki was originally made from hemp to protect against pirates intercepting gifts sent from the continent. Mizuhiki was introduced to Japan in the Heian period (794-1185) in simplified form, its use limited to the royal family until it was made available to the public in the Edo period (1603-1868). It was only during the Taisho period (1912-1926) that it developed into the decorative art one associates it with today.

Kanazawa lays claim to Japan’s best-known, most innovative mizuhiki, thanks to the efforts of a local artisan named Sokichi Tsuda (1869-1943). Tsuda was responsible for expanding the flat mizuhiki art form and folding techniques usually used with gift envelopes to three-dimensional mizuhiki that are resplendent, highly creative, and sometimes very elaborate.

The Tsuda Mizuhiki Orikata Shop

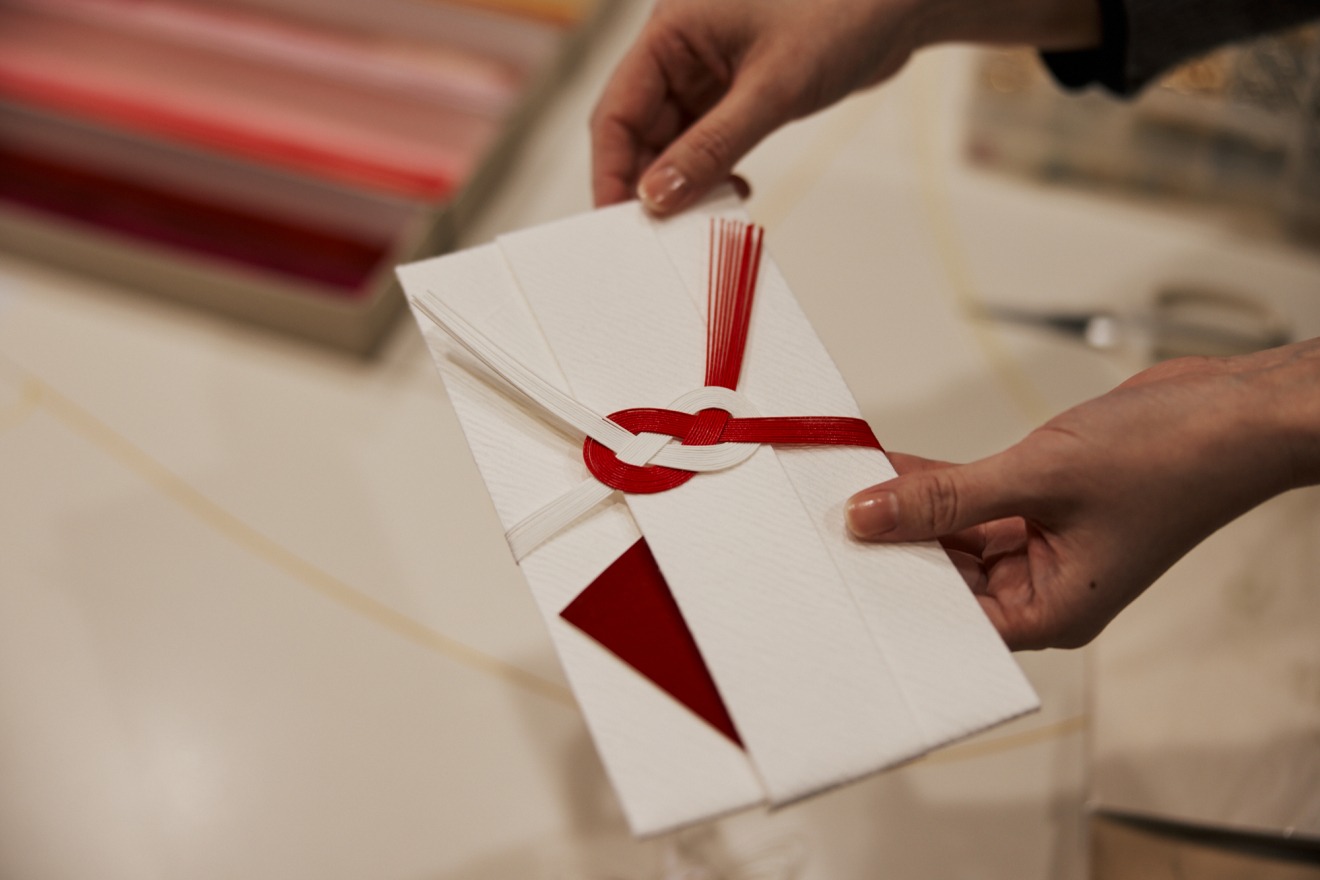

Sokichi Tsuda founded the Tsuda Mizuhiki Orikata shop in 1915, immediately becoming Kanazawa’s premier mizuhiki artist and purveyor. He began his business by focusing on yuino – a formal gift exchange between families in a Japanese traditional engagement ceremony, which some Kanazawa families continue to follow today. At Tsuda Mizuhiki Orikata, you will find the sixth generation of Tsuda-family mizuhiki artists producing yuino-kazari engagement decorations, as well as kinpu decorative envelopes, in the three-dimensional styles that Sokichi Tsuda made famous over a century ago.

The first floor of Tsuda Mizuhiki Orikata is divided into a work area for professional mizuhiki artisans, whom visitors can watch ply their skills, and a giftshop well worth spending time in. Traditional mizuhiki items displayed and sold in the shop include wedding-themed designs as well as decorative items to brighten one’s home or office, such as plum and pine trees; small lanterns; wind chimes; an array of birds, animals, and dragons; samurai in armor; and – especially popular – women’s accessories. Also lining a wall and sold here are traditional yuso and shugi envelopes used for monetary gifts. And mizuhiki-origami gift wrapping, tied with elaborate mizuhiki designs and written with calligraphy describing the gift-giver’s feelings, remains a mainstay for special events and is also available here.

The Workshop

In addition to its unique products, Tsuda Mizuhiki Orikata offers visitors a hands-on mizuhiki workshop, a fun introduction to an art form seen often in Japan, especially in Kanazawa. It’s yet another cultural treasure whose origin and artistry developed in Kanazawa, and visitors are lucky that they can access it as easily as this!

The workshop is held on the shop’s second floor, before a small gallery of works by Tsuda Sokichi and a collection of old mizuhiki designs and materials from earlier periods. On the day I joined the workshop, I was given a choice of what to make from a design menu; I opted for a flower mizuhiki. On the table before me lay a box containing long colored strings, and it was from these that I embarked on my design.

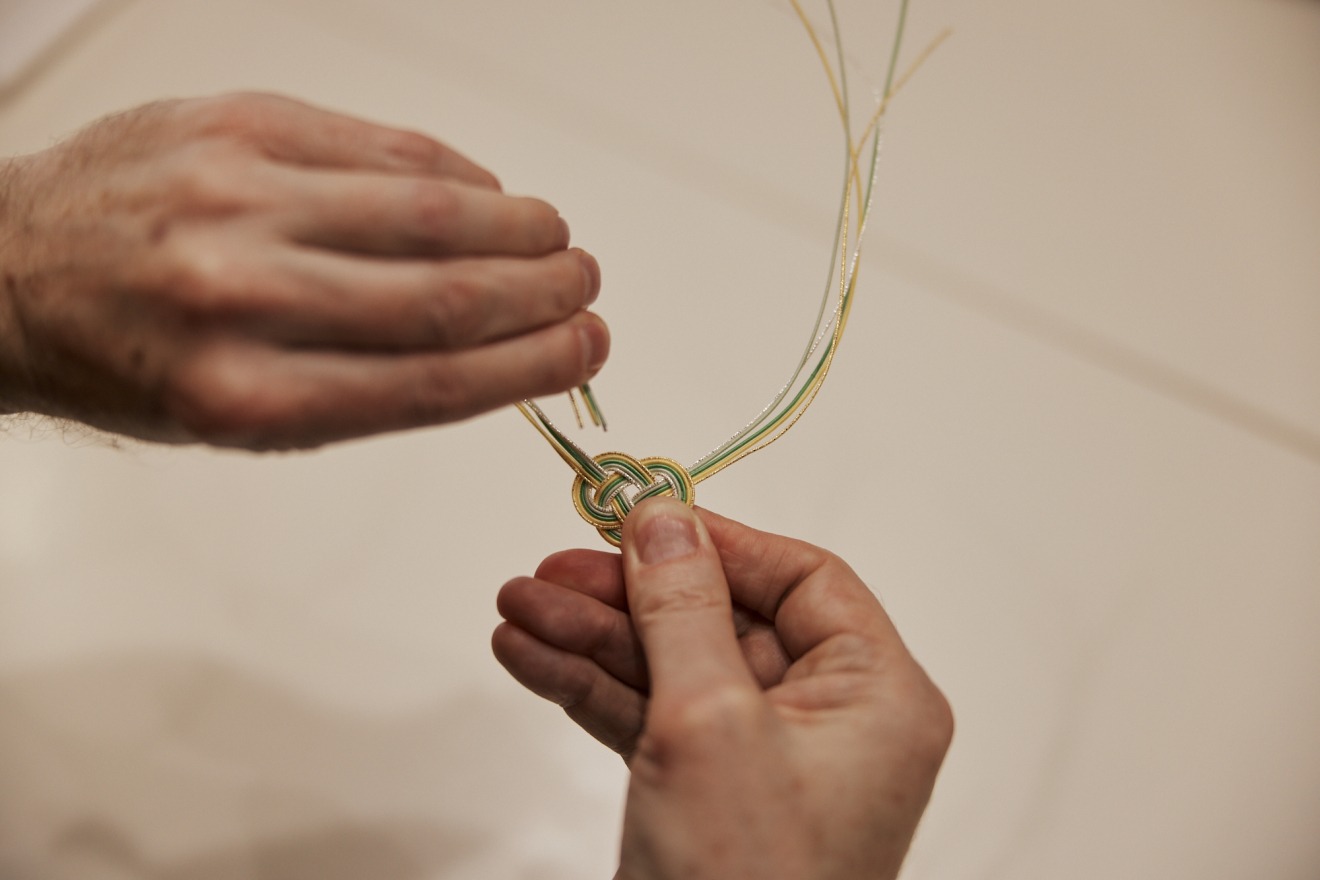

After choosing five colored strings – shiny gold, subdued gold, dark green, light green, and sparkling silver – I used a small tool to press the strings as I pulled them from end to end between my thumb and index finger. Afterward, the strings felt lighter, “bendier,” and easier to work with. I again pinched my strings between thumb and index finger, then smoothed them out so each one stretched out without overlapping.

It was now time to make a loop of my aligned strings, the easiest of all the loops I needed to make. Looping them even once caused them to fall out of alignment, and I had to pluck them back into sequence with my fingernails, then use the pads of my thumb and index finger to “iron” them out again. After configuring two more loops, a “flower” such as I was supposed to end up with – but still too big and whose strings had come loose again – was starting to emerge. Once again, I pulled each string closer together until they lay firmly on top of each other, then plucked them into proper sequence before “ironing” them out again with the pads of my thumb and index finger.

Soon I had fashioned five of my flower’s petals, but with spaces between my strings. Pulling tight each string and smoothing it out helped shape my mizuhiki flower properly, and a small space in the middle of my flower was a good sign, I was told. It was through this space that I had to pull my tightly aligned colored strings, then I repeated the process a second time. Thank goodness my instructor was there to repair my mizuhiki, though I was encouraged by the extent to which I had succeeded with my task – everything felt small between my fingers and was hard to keep aligned.

The whole process felt like solving a puzzle, and though difficult at times, it became increasingly exhilarating as I progressed. Watching the instructor fix my mistakes with practiced ease and efficiency was like watching someone perform magic before my eyes. Someone who had accompanied me asked half-jokingly if I intended to make this my new hobby, and the idea actually struck me as very appealing.

Tsuda Mizuhiki Orikata is an under-the-radar experience visitors won’t soon forget. To be able to make an item as unique and beautiful as a mizuhiki flower, for instance, brings one closer to the heart and soul of Kanazawa, a city rightly famous for its refined artisan culture. And what better way to form good memories of your Kanazawa experience than by making your own mizuhiki design to take home with you?

Text by Novelist David Joiner

Photo by Nik van der Giesen