Goldbeating: The hardcore pummeling at the heart of Kanazawa gold leaf

In samurai times, the Kaga Domain was second only to the shogun overlords in terms of wealth. Ruled by the Maeda clan, it was a sprawling territory on the Sea of Japan with vast rice production. The Maeda warlords patronized artisans who specialized in one of the most exquisite craft heritages of feudal Japan: gold leaf.

Gold leaf is gold that has been hammered down into wafer-thin sheets. It is seen on folding screens, lacquerware, boxes, bowls, statues, Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines (for instance, Kyoto’s Kinkakuji and Nikko’s Toshogu), as well as edible decoration for food.

caption: One of Japan’s most iconic temples, Kinkakuji in Kyoto, is covered in gold leaf

Kanazawa, the ancestral seat of the Maeda clan, has long been Japan’s main center of production of gold leaf, or kinpaku. Even the city’s name is golden: Kanazawa means “gold marsh” and comes from the fact that gold was found upstream from the Saigawa River. Here, artisans continue to manufacture gold leaf with methods that rely on manual labor, natural materials, machinery and countless repetitions to ensure a high-quality product that has a luster and soft appearance.

A gold leaf production technique called entsuke was developed some four centuries ago in Kanazawa. Entsuke means “framed” and refers to the fact that gold leaf squares are set on and “framed” by washi paper when sold. Entsuke centers on the use of special foil-beating paper sheets (uchigami) that are gathered into a book and bound with leather. Traditional Japanese washi handmade paper that has been soaked in lye and persimmon tannins is used for the uchigami. They are very smooth and perfect for stretching out gold leaf under pressure.

caption: Craftsman Noriyuki Matsumura prepares a book of foil-beating paper for hammering

“The key is that this washi paper is made with a special mineral blend, without which the gold leaf cannot be spread out properly,” says Ken-ichi Matsumura, a master gold leaf craftsman and the head of Matsumura Seihakusho, a metallurgy company in an area of gold leaf makers north of Kanazawa Station. “Without this washi, the gold leaf cannot become as thin as we make it.”

The workshop reverberates with the sound of machine hammers. The entsuke process begins with gold leaf sheets that have already been flattened by machine. Matsumura and his son Noriyuki clean the foil-beating books and then fill them with the gold sheets, inserting small slivers of gold between 1,800 sheets of paper. It’s slow, painstaking work but there are no shortcuts.

caption: Craftsman Ken-ichi Matsumura demonstrates how gold leaf is beaten under a machine hammer

When the books are complete, they go under a goldbeating machine, a blackened tool of hammers, pulleys, wheels and induction motors that looks 100 years old. Here they are repeatedly pounded for at least half a day. The sheets are transferred into yet another book before undergoing more pounding. When the sheets are flattened as much as possible, the hammering is done.

caption: A craft worker at Matsumura Seihakusho prepares to cut the hammered gold leaf into squares

The result is gold leaf as thin as one ten-thousandth of a millimeter. It’s a delicate, gauzelike material that must be handled with great care to prevent tearing and crumpling and to protect them from static electricity.

On the second floor at Matsumura Seihakusho, another worker uses special bamboo implements to gently remove the gold leaf from a hammered book. She lays it on a cutting board and blows it flat. The gold ripples under her breath like liquid.

caption: Special bamboo implements are used to prevent tearing and crumpling

The gold leaf is then individually trimmed into 109-milimeter squares with a traditional bamboo cutter called a takewaku. The trimmings are saved in a box and will be used for other gold leaf products.

The cut squares are again gently manipulated with bamboo, from which they hang like silk. They are carefully placed on a bed of washi paper made from the mitsumata plant to prepare for shipping to wholesalers. The finished product exudes a warm glow. Its quality is the result of many steps, repeated many times in a process that takes about two weeks.

caption: Finished entsuke gold leaf is one ten-thousandth of a millimeter thick and cut into 109-milimeter squares

The recipient of many craft awards, Matsumura has made gold leaf for over 40 years, inheriting the skills from his father. To preserve this knowledge, he established the Society for the Preservation of Traditional Kanazawa Gold Leaf, assuming the position of chairman.

The work of craftspeople like the Matsumuras was recognized when UNESCO included entsuke gold leaf on its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

There are only about 15 entsuke households like Matsumura’s left in Kanazawa. There were perhaps hundreds or thousands of these households 100 years ago, when machine tools were introduced to the industry. Today, Matsumura’s gold leaf association is working with global jeweler Tiffany & Co. to help train future entsuke artisans.

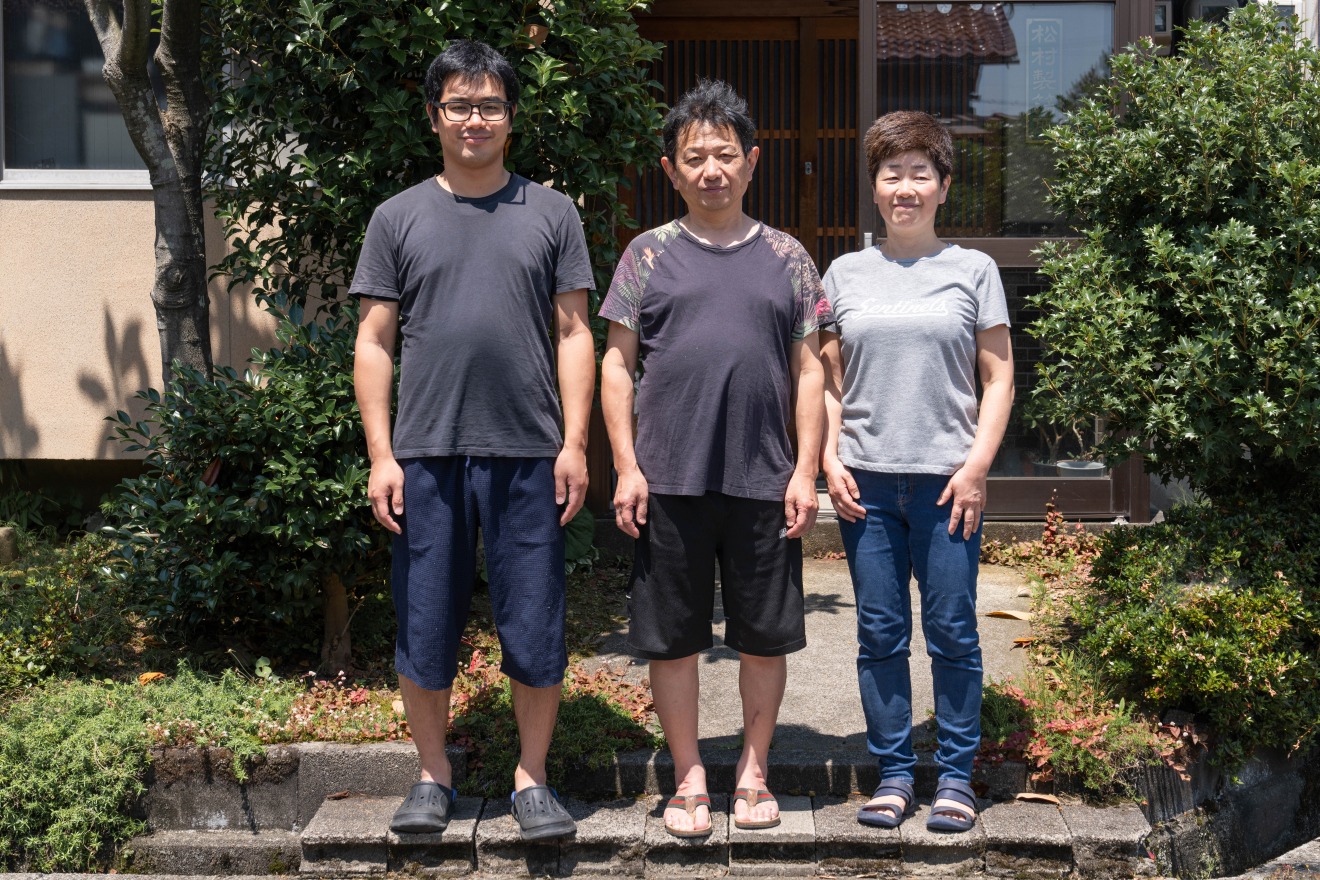

caption:The Matsumura family pose outside their workshop in Kanazawa

“The average age of these craftsmen in over 70, so I’m worried about the future,” says Matsumura. “I hope to preserve this craft and pass it on to future generations.”

To learn more about traditional Kanazawa gold leaf, stop by the Kanazawa Yasue Gold Leaf Museum, founded by craftsman Yasue Takaaki (1898-1997). It covers the history and production techniques of the art, and has about 300 pieces, mostly Japanese works starting from the Edo period (1603–1868) up to today. They include folding screens, hanging scrolls, ceramics, lacquerware, Noh costumes and Buddhist altars.

caption: The Kanazawa Yasue Gold Leaf Museum exhibits both gold leaf production tools and artworks Images of the Kanazawa Yasue Gold Leaf Museum courtesy of Kanazawa City