KANAZAWA TRADITIONAL THEATER: KAGA HOSHO NOH

“A man’s life has an end, but there is no end to the pursuit of Noh.”

So said the great Noh actor, writer, and theorizer Zeami (1363-1443). There’s no disputing the first part of this statement, and while for some people, especially in contemporary times, the pursuit of Noh has no beginning, Kanazawa has done much to make that pursuit possible. For those who are passionate about Noh – and in Kanazawa there are thankfully still many such people – that pursuit can know no bounds.

Although many visitors to Japan may have heard or perhaps even seen a performance of Noh – one of the oldest performing arts in the world – few know it well, and fewer still are familiar with the Kaga Hosho of Noh theater. As a theatrical performance, Noh combines dance, drama, music, and chanting. It was first developed in the Heian period (794-1185) before becoming established in its current form, along with Kyogen (comical Noh), in the Edo period (1603-1868).

It was during Edo times, under the auspices of the Maeda lords of the Kaga domain (present-day Ishikawa prefecture), that Kaga Hosho Noh came into existence. For most of the Edo period, the Maeda family promoted Noh as a samurai entertainment while also encouraging it, in the form of Kaga Hosho, as an entertainment that ordinary citizens of Kaga could enjoy. With the advent of the Meiji period in 1868 , and as Japan began to modernize and embrace Western culture, Kaga Hosho nearly disappeared. However, the efforts of a Kanazawa man named Sano Kichinosuke helped ensure that this group of Noh lived on. In fact, it is almost entirely thanks to his efforts that Kaga Hosho is now designated as an Intangible Cultural Asset by the city of Kanazawa.

For Noh beginners and long-time enthusiasts, the Kanazawa Noh Museum is a great place to learn about Kaga Hosho Noh. Only a few steps from both the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art and Kenrokuen garden, this museum offers not only fascinating and extensive information about Noh theater, but also the chance to don elaborate Noh costumes, including carved wooden masks, and channel their inner Zeami.

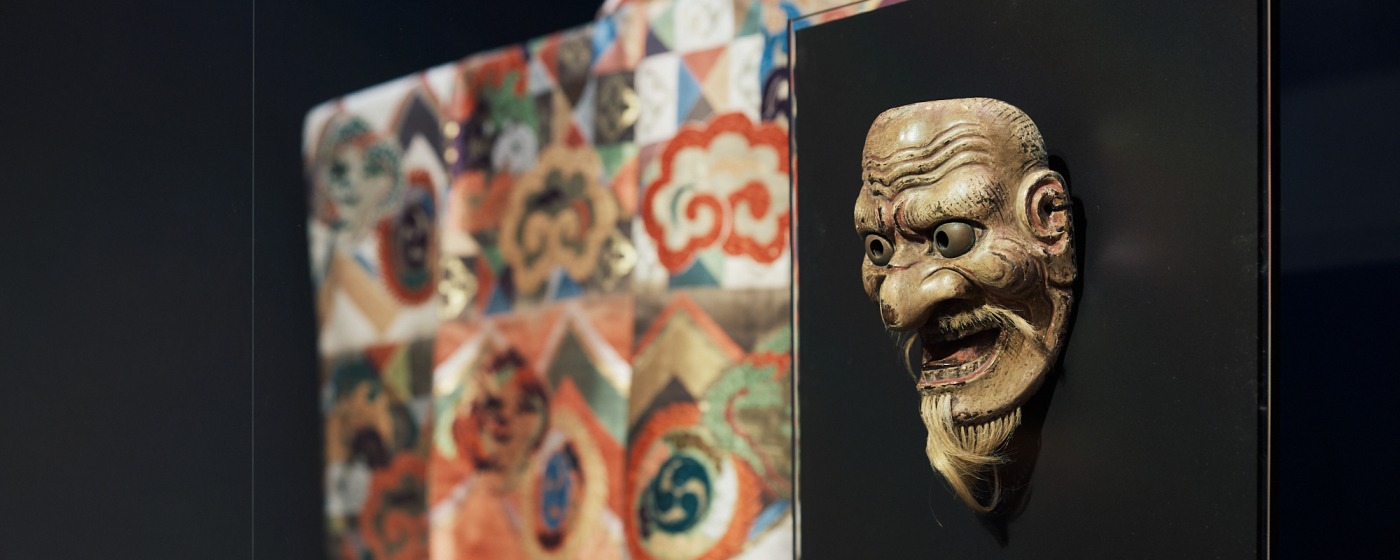

Entering the museum, one is immediately transported to the world of Noh. Lively music from Noh performances – a heady combination of the Japanese fue flute, tsuzumi hand drums, taiko drums, and Noh chanting – welcomes visitors as they walk through the spacious learning and display areas, and one can’t help making (or averting) eye contact with the many expressive Noh masks exhibited.

Special floor tiles depicting musical instruments used in Noh as well as various stage elements lead visitors in a loop around the exhibition area. Panels in Japanese and English give helpful summaries of stage design, character types, and musical accompaniment in Noh performances, and there is even a large screen on which Noh mask expressions and dance forms are shown and explained. If you’ve ever wondered how a Noh mask is created, there is a display and explanation area for that, too, with examples of tools, paint, and lacquer used in their production.

A highlight for many visitors is a tatami-floored space – the Noh costume experience corner – where one can directly enter the world of Noh actors by donning an elaborate stage costume, and try an authentic Noh mask on for size (literally!) while standing before a pine tree screen that brings an actual Noh stage to life.

While there’s much to see and do on the museum’s first floor, the second floor contains a larger exhibition room in which visitors will find must-see objects related to the artistic world of Kaga Hosho Noh. Stunning Noh costumes, in all their complexity and astounding craftsmanship, and which date as far back as the Edo period (1603-1868), are beautifully displayed here, including elaborate wigs and crowns, colorful books of Noh illustrations, beautifully brocaded costumes, obi sashes, choken jackets, surihaku, nuihaku, and maiginu robes, and books of Noh lyrics. Another reason to devote time to this floor is to see the masterfully carved masks (made from Japanese cypress) on display that reflect Noh’s grand panoply of memorable characters, human and nonhuman alike. Perhaps the most impressive of these masks is also the oldest, a wonderfully preserved “Hanya” (female demon) Noh mask carved in the 16th century during Japan’s Momoyama period.

Before exiting the second floor, be sure to enter the video room to view a short historical documentary on Kaga Hosho Noh. And spend at least a few minutes in the Noh and Kyogen Picture Book Area, which is especially popular among children.

The third floor can also be visited, and if you’re lucky you’ll be able to join a seminar held here about Noh or watch Kanazawa children gather to learn Kaga Hosho Noh.

- Kanazawa Noh Museum

-

- more

ISHIKAWA PREFECTURAL NOH THEATER: KAGA HOSHO NOH

If you plan your visit to Kanazawa right, you can easily catch a Noh performance at the Ishikawa Prefectural Noh Theater just up the road from the Kanazawa Noh Museum.

Built in 1972, when it became the first independent public Noh theater in Japan, this venue regularly puts on well-known Noh and Kyogen performances – some of which outdate Shakespearean dramas by 200 years. In the “Evening of Winter Noh Performance” that I attended, which was shortened to around two hours, it was possible to watch for an advance fee of ¥1000 (US$7). In regular Noh performances, such as those that the Kanazawa Noh Theater Association organizes, the fees differ and the duration of the performances (comprising Noh, Kyogen, and a total of three acts) often exceeds two hours. Affordable ticket prices are made possible by national and local government grants, a sign of the importance given today to Noh theater and Kaga Hosho Noh.

The theater hardly rests on its laurels, however, but continues to strive to make Noh performances more accessible to theatergoers and thus more entertaining. For non-Japanese visitors, the theater has made remarkable efforts to produce translations of each performance and a range of supporting Noh material into English. One example of this is the option for visitors to use an electric tablet on which, in Japanese and English, the play’s characters are listed and a detailed summary of the play appears, including “highlights” of the first and second acts as well as explanations of the play’s deeper meanings and possible ways to interpret the story. The theater also offers a smartphone option to access the same information. And for each performance, the theater provides a printed “storyline” in English, which details the action in each scene and also gives a short history of the performance, while explaining its significance within the Noh canon.

The theater only has general audience seating, so if you want the best seat, plan to arrive early. Seats are comfortable, and the seating area is small enough that the viewing experience is an intimate one. No seating is far from the stage, which is fortunate because the stage is worth seeing in all of its simple magnificence. Built 40 years before the existence of the theater in which it is housed, the stage is divided into four parts – the main stage, corridor, chorus area, and musicians’ seating – with a large pine tree painted on the back wall of the main stage to represent the means by which the heavens passed Noh down to humankind.

Also, you will notice that many Noh theatergoers dress to the hilt; one often sees men and women in formal kimono, though usually they are the older crowd – and it’s an older crowd in general that makes up the audience.

Be aware that, unlike in western theater, there is no “when the lights go down” moment before the play starts. Visitors are cued in to the start of the play when music begins from behind the stage. Lights are never dimmed, and no spotlights are ever used. There is only normal stage and theater lighting before, during, and after the performance.

The theater’s Noh schedule runs all year, and a surprising range of performances are staged seasonally. I most recently attended an “Evening of Winter Noh Performance” featuring the play Kurozuka, which was preceded by the more lighthearted Kyogen skit Haratatezu. Like many Noh plays, Kurozuka is dramatic, has clear Buddhist overtones, and involves a nonhuman character – in this case, a demon who pretends to be a beautiful woman living alone in the mountains. Haratatezu is a shorter, comical performance about two temple maintainers who come across a bumbling traveling monk and ask him to become the abbot of their temple. Again, even in comedy, one often finds in Kyogen themes at least tangentially related to Buddhism (or even to Shintoism).

On-stage in Kaga Hosho Noh, there are usually musicians and a chorus of Noh chanters in the background, and the actors’ costumes can sometimes be elaborate – and when they are, they’re a feast for the eyes – while their movements are always deliberate and highly stylized. As in Kurozuka, the appearance of nonhuman characters, such as the female demon in this play, are exciting and memorable, particularly when the human characters are forced to confront them with life-or-death consequences.

Kaga Hosho Noh has continued into the present from the dawn of Japanese stage performance, and seeing such drama in a contemporary setting, such as at the Ishikawa Prefecture Noh Theater, is an experience unlike any other. The Ishikawa Prefecture Noh Theater has gone out of its way, incorporating modern technology unobtrusively whenever possible, to make Kaga Hosho Noh accessible to all-comers. Kaga Hosho Noh is unforgettable and extremely easy to experience in Kanazawa.

For more information on the theater’s performance schedule and to reserve tickets, be sure to visit here.