Travel Back to Edo Times in the Hashiba District: samurai home and garden, wooden sweet molds, and Ohi-ware

Samurai Residence: Kurando Terashima's House

Kanazawa is deservedly famous for many things. Among them are its well-preserved samurai history and its beautifulhistoric gardens.

Although the city’s most notable samurai enclave is in the Nagamachi district, sitting quietly across the city in the Hashiba district is Kanazawa’s most authentic samurai residence – a Kanazawa City Designated Cultural Property known as "Samurai Residence: Kurando Terashima's House.

” Not only is the house historically important, but people in the know flock to its garden year-round to admire it.

Kurando Terashima’s house was built by his grandfather in the late 1700s. It was grander during the period when the Terashima family served as mid-level samurai in the Maeda domain, evidenced by a blueprint of the house on the first floor, but has since been reconstructed on a smaller scale.

Kurando’s refined aesthetics are evident inside and outside the house. On the first floor are several Japanese-style rooms, including one used for the tea ceremony and one for playing the koto. The tea ceremony room was designed to enjoy tea with a view of the strolling garden, noted in part for its dry pond. Adorning the walls of some rooms are paintings Kurando made, which contributed to his enduring reputation as an artist. A small exhibition room is located near the entrance, and even today the “nightingale” wooden floor that leads to it – a feature in samurai homes akin to contemporary house alarms – “sings” as you walk across it. The second story, which contains a room overlooking the garden that Terashima reserved for his painting, is off-limits to visitors.

Although the house has changed over the years, the garden remains as it was during Kurando’s lifetime, with over 200 trees and assorted flowers, including camellia, kerria, Coptis japonica, hardy begonia, tea, and wintersweet.

Though original in many ways, the garden is, like Kanazawa’s famous Kenrokuen, a strolling landscape garden, designed to be appreciated in all four seasons. In spring, 300-year-old azaleas known locally as dodan tsutsuji bloom in profusion, their branches lit with white blossoms that brighten the garden. In summer, a cooling green radiates from the leaves of trees and a carpet of cultivated moss. In fall, the foliage turns deep red and gold, and the varieties of maple are at their most spectacular. And in winter, the garden’s trees are strung with protective yukitsuri ropes, while their branches and the ground and stone lanterns beneath them are often covered in pure white layers of snow.

In 1825, Kurando was dismissed from his position as a Maeda retainer, and 12 years later was exiled to Notojima Island for criticizing the clan’s policies. He died six months later. Nearly 50 years after his death, the Maeda family acknowledged Kurando’s achievements, restoring his reputation and honor. Today he is known as a hero to the people of Kanazawa.

The Terashima house is closed on Tuesdays and over New Year’s but is otherwise open year-round. General admission is ¥310; for an additional ¥350 you can enjoy tea and traditional rakugan sweets served in the Terashima family’s former kansen tea room.

Morihachi Sweets and Wooden Sweet Molds Museum

Although Morihachi is one of Japan’s oldest and most famous makers of wagashi (traditional Japanese sweets), their Wooden Sweet Molds Museum – the only such museum in Japan – is one of Kanazawa’s lesser-known gems.

Formuseum-goers, it’s perhaps the city’s best-kept secret.

Morihachi has several stores in Kanazawa, but its main store in the Hashiba district, midway between Kenrokuen and the Higashi-chaya district, is easily its most impressive. In addition to its extensive confectionary selection and gift shop on the first floor, its second floor is devoted to a Japanese-style café, a workshop where visitors can learn how to make rakugan (pressed sugar and rice flour shaped by molds), one of Kanazawa’s best collections of Kutani- and Kokutani-ware, and a wooden sweet-molds museum unlike any other museum in Japan.

Morihachi has been operating continuously in Kanazawa since 1625, when Maeda Toshitsune, the third lord of the Kaga domain (present-day Ishikawa prefecture), ordered Morishitaya Hachizaemon to start a confectionary business to serve the newly established domain. Through Morishitaya’s efforts, the Morihachi confectionary business was born.

Morichachi’s reputation and fame has grown since its inception, and at various times has even served at the request of Japan’s imperial family.

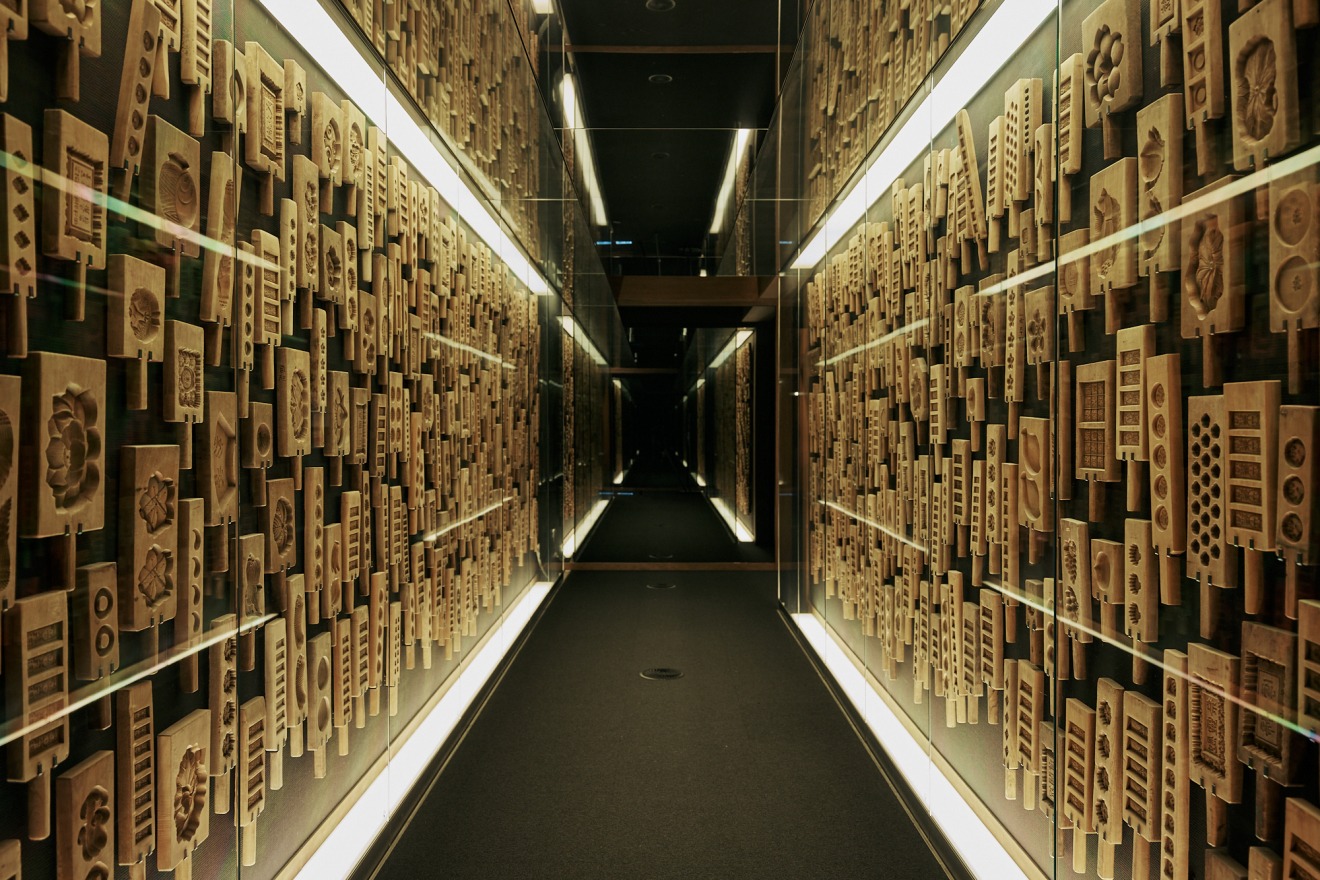

But the centerpiece of the main store is its museum on the second floor. One enters it through a narrow “wooden molds tunnel” whose dark walls are hung with molds made from yamazakura (mountain cherry) wood, illuminated to show off their detailed craftmanship and variety of designs. Most share a rectangular “battledore” shape, with a handle at the base.

At the end of the corridor, visitors encounter a massive room displaying over 1000 wooden sweet molds.

Without exception, the molds are masterpieces of carving that depict animals, insects, flowers, trees, foods, landscapes, people, and even Noh masks, among other ingenious designs. As visitors navigate the molds along each wall, the artisans and histories of many molds are explained in Japanese and English. The molds proceed in chronological order, starting with the Edo period (1603-1868) and ending with the Showa period (1926-1989), when they reached their height of popularity with the general populace: Kanazawa families, students, temples and shrines, companies and government organizations, and even a local infantry regiment before the end of World War II.

Upon exiting the museum, visitors find themselves before the Morihachi café, which contains a chashitsu tearoom, rakugan workshop, and wall of windows overlooking the beautiful garden of Kurando Terashima’s House.

But the centerpiece of the main store is its museum on the second floor. One enters it through a narrow “wooden molds tunnel” whose dark walls are hung with molds made from yamazakura (mountain cherry) wood, illuminated to show off their detailed craftmanship and variety of designs. Most share a rectangular “battledore” shape, with a handle at the base.

At the end of the corridor, visitors encounter a massive room displaying over 1000 wooden sweet molds. Without exception, the molds are masterpieces of carving that depict animals, insects, flowers, trees, foods, landscapes, people, and even Noh masks, among other ingenious designs. As visitors navigate the molds along each wall, the artisans and histories of many molds are explained in Japanese and English. The molds proceed in chronological order, starting with the Edo period (1603-1868) and ending with the Showa period (1926-1989), when they reached

their height of popularity with the general populace: Kanazawa families, students, temples and shrines, companies and government organizations, and even a local infantry regiment before the end of World War II.

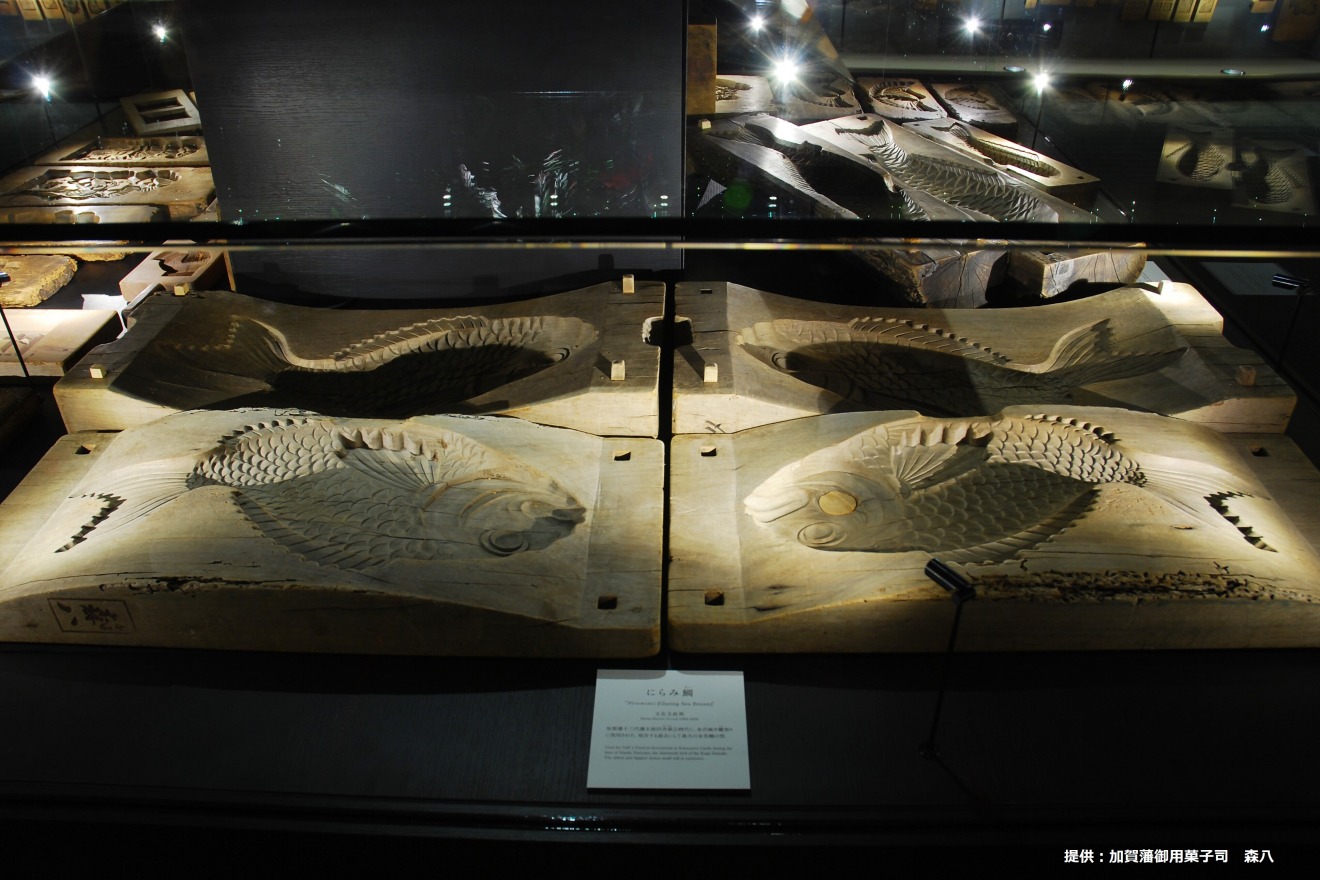

In the center of the room is a large display case in which the oldest molds are featured, including the “Niramidai “Glaring Sea Bream, which is also the museum’s largest mold. A single wall near the exit is devoted to iron objects once used to brand letters or patterns into manjuu (steamed buns), senbei (rice crackers), and sponge cakes.

Many of these, too, can be traced back to the Edo period.

Upon exiting the museum, visitors find themselves before the Morihachi café, which contains a chashitsu tearoom, rakugan workshop, and wall of windows overlooking the beautiful garden of Kurando Terashima’s House.

The workshop costs ¥1650 and requires a reservation two days in advance, but if you’re short on time and are happy to eat sweets made by some of the best-trained traditional sweets-makers in Japan, the café’s menu is extensive and offers not only tea but, in a nod to modern tastes, coffee as well. No reservations are needed for the café.

Ohi Gallery and Museum

Opposite Morihachi’s main store is the Ohi Gallery and Museum, which showcases Ohi-ware pottery and ceramics dating from the same era that Morihachi was established. The front building is the residence of Ohi Chozaemon XI (b. 1958).

An Edo-period structure, it boasts a 500-year-old pine tree called Orizuruno Matsu (“Origami Crane Pine”), which the City of Kanazawa has designated a historical landmark, as well as a small garden designed by world-famous Sogetsu ikebana grandmaster Teshigawara Hiroshi.

In 1666, the Kaga lord Maeda Tsunanori invited Uransenke tea master Senso Soshitsu – a descendant of Senno Rikyu, originator of Japan’s modern tea ceremony – to come to Kanazawa from Kyoto. Accompanying him was a potter named Chozaemon Hodoan, who would soon establish Ohi-ware in Kanazawa and take the name Ohi Chozaemon I.

For the next two centuries, six generations of the Ohi Chozaemon line would make Ohi-ware exclusively for Maeda clan tea ceremonies. It was only near the end of the Edo period, when the daimyo system collapsed, that Ohi-ware became available to the public.

Traditional Ohi-ware has several distinctive qualities. The clay used in Ohi-ware comes from an area of Kanazawa called Ohi.

Manipulated by hand rather than a potter’s wheel, Ohi-ware is further shaped with traditional tools before being fired in a kiln for a short time at high heat, then cooled rapidly. Once cool, an iron-rich glaze called amegusuri is applied. Together with the mineral composition of Ohi clay and the heat at which it’s fired, the works take on a unique amber finish.

Ohi Toshio Chozaemon XI (b. 1958) is the current Ohi-ware master, having succeeded his father, Ohi Chozaemon X, in 2016.

In his work he brings ingenuity to the fore, combining tradition and innovation to ensure the continuation and relevance of Ohi-ware. Raised in Kanazawa and educated at Boston University, he lives and works in Kanazawa, traveling often to teach, exhibit, and collaborate with top artists.

In 2023 the Emperor of Japan bestowed on him the Imperial Prize/Japan Art Academy Award, while his father, in 2011, received from the Emperor the Order of Cultural Merit; both awards represent the country’s highest level of cultural achievement.

The Ohi Gallery was designed by internationally acclaimed architect Kengo Kuma.

The Ohi Museum, which sits behind the main building, is a modern three-storied structure that exhibits, in both English and Japanese, the nearly 360-year history of Ohi pottery. On display are works by eleven generations of Ohi Chozaemon, including several by Ohi Chozaemon I, as well as other objects related to the history and manufacture of Ohi-ware.

On the third floor one finds larger, more modern works of highly accomplished glazed pottery.

General admission to the Ohi Gallery and Museum is ¥700 for adults, and the café, where one can enjoy Japanese wagashi sweets and traditionally made green tea in tea bowls hundreds of years old, costs another ¥800 (¥1500 total).

For visitors who wish only to try tea and sweets without entering the museum, the fee is ¥1000.A more expensive “premium package,” reserved in advance, includes experiencing Japanese tea ceremony with Chozaemon Toshio Ohi XI in a beautiful tearoom set behind sliding doors layered with Kanazawa gold leaf. The gift shop is free to enter and shop in.

Text by Novelist David Joiner

Photo by Nik van der Giesen